[1] Albert, called by God’s favour to be Patriarch of the Church of Jerusalem, bids health in the Lord and the blessing of the Holy Spirit to his beloved sons in Christ, B. and the other hermits living under obedience to him, who live near the spring on Mount Carmel.

[2] Many and varied are the ways in which our saintly forefathers laid down how everyone, whatever his station or the kind of religious observance he has chosen, should live a life of allegiance to Jesus Christ – how, pure in heart and stout in conscience, he must be unswerving in the service of the Master.

[3] It is to me, however, that you have come for a rule of life in keeping with your avowed purpose, a rule you may hold fast to henceforward; and therefore:

[4] The first thing I require is for you to have a Prior, one of yourselves, who is to be chosen for the office by common consent, or that of the greater and maturer part of you. Each of the others must promise him obedience – of which, once promised, he must try to make his deeds the true reflection – and also chastity and the renunciation of ownership.

[5] If the Prior and the brothers see fit, you may have foundations in solitary places, or where you are given a site suitable and convenient for the observance proper to your Order.

[6] Next, each one of you is to have a separate cell, situated as the lie of the land you propose to occupy may dictate, and allotted by disposition of the Prior with the agreement of the other brothers, or the more mature among them.

[7] However, you are to eat whatever may have been given you in a common refectory, listening together meanwhile to a reading from Holy Scripture where that can be done without difficulty.

[8] None of the brothers is to occupy a cell other than that allotted to him, or to exchange cells with another, without leave of whoever is Prior at the time.

[9] The Prior’s cell should stand near the entrance to your property, so that he may be the first to meet those who approach, and whatever has to be done in consequence may all be carried out as he may decide and order.

[10] Each one of you is to stay in his own cell or nearby, pondering the Lord’s law day and night and keeping watch at his prayers unless attending to some other duty.

[11] Those who know how to say the canonical hours with those in orders should do so, in the way those holy forefathers of ours laid down, and according to the Church’s approved custom. Those who do not know the hours must say twenty-five ‘Our Fathers’ for the night office, except on Sundays and solemnities when that number is to be doubled so that the ‘Our Father’ is said fifty times; the same prayer must be said seven times in the morning in place of Lauds, and seven times too for each of the other hours, except for Vespers when it must be said fifteen times.

[12] None of the brothers must lay claim to anything as his own, but you are to possess everything in common; and each is to receive from the Prior – that is from the brother he appoints for the purpose – whatever befits his age and needs.

[13] You may have as many asses and mules as you need, however, and may keep a certain amount of livestock or poultry.

[14] An oratory should be built as conveniently as possible among the cells, where, if it can be done without difficulty, you are to gather each morning to hear Mass.

[15] On Sundays too, or other days if necessary, you should discuss matters of discipline and your spiritual welfare; and on this occasion the indiscretions and failings of the brothers, if any be found at fault, should be lovingly corrected.

[16] You are to fast every day, except Sundays, from the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross until Easter Day, unless bodily sickness or feebleness, or some other good reason, demand a dispensation from the fast; for necessity overrides every law.

[17] You are to abstain from meat, except as a remedy for sickness or feebleness. But as, when you are on a journey, you more often than not have to beg your way, outside your own houses you may eat foodstuffs that have been cooked with meat, so as to avoid giving trouble to your hosts. At sea, however, meat may be eaten.

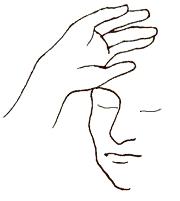

[18] Since man’s life on earth is a time of trial, and all who would live devotedly in Christ must undergo persecution, and the devil your foe is on the prowl like a roaring lion looking for prey to devour, you must use every care to clothe yourselves in God’s armour so that you may be ready to withstand the enemy’s ambush.

[19] Your loins are to be girt with chastity, your breast fortified by holy meditations, for as Scripture has it, holy meditation will save you. Put on holiness as your breastplate, and it will enable you to love the Lord your God with all your heart and soul and strength, and your neighbour as yourself. Faith must be your shield on all occasions, and with it you will be able to quench all the flaming missiles of the wicked one: there can be no pleasing God without faith; and the victory lies in this – your faith. On your head set the helmet of salvation, and so be sure of deliverance by our only Saviour, who sets his own free from their sins. The sword of the spirit, the word of God, must abound in your mouths and hearts. Let all you do have the Lord’s word for accompaniment.

[20] You must give yourselves to work of some kind, so that the devil may always find you busy; no idleness on your part must give him a chance to pierce the defences of your souls. In this respect you have both the teaching and the example of Saint Paul the Apostle, into whose mouth Christ put his own words. God made him preacher and teacher of faith and truth to the nations: with him as your teacher you cannot go astray. We lived among you, he said, labouring and weary, toiling night and day so as not to be a burden to any of you; not because we had no power to do otherwise but so as to give you, in your own selves, as an example you might imitate. For the charge we gave you when we were with you was this: that whoever is not willing to work should not be allowed to eat either. For we have heard that there are certain restless idlers among you. We charge people of this kind, and implore them in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ, that they earn their own bread by silent toil. This is the way of holiness and goodness: see that you follow it.

[21] The Apostle would have us keep silence, for in silence he tells us to work. As the Prophet also makes known to us: Silence is the way to foster holiness. Elsewhere he says: Your strength will lie in silence and hope. For this reason I lay down that you are to keep silence from after Compline until after Prime the next day. At other times, although you need not keep silence so strictly, be careful not to indulge in a great deal of talk, for as Scripture has it – and experience teaches us no less – Sin will not be wanting where there is much talk, and He who is careless in speech will come to harm; and elsewhere: The use of many words brings harm to the speaker’s soul. And our Lord says in the Gospel: Every rash word uttered will have to be accounted for on judgment day. Make a balance then, each of you, to weigh his words in; keep a tight rein on your mouths, lest you should stumble and fall in speech, and your fall be irreparable and prove mortal. Like the Prophet, watch your step lest your tongue give offence, and employ every care in keeping silent, which is the way to foster holiness.

[22] You, brother B., and whoever may succeed you as Prior, must always keep in mind and put into practice what our Lord said in the Gospel: Whoever has a mind to become a leader among you must make yourself servant to the rest, and whichever of you would be first must become your bondsman.

[23] You other brothers too, hold your Prior in humble reverence, your minds not on him but on Christ who has placed him over you, and who, to those who rule the Churches, addressed these words: Whoever pays you heed pays heed to me, and whoever treats you with dishonour dishonours me; if you remain so minded you will not be found guilty of contempt, but will merit life eternal as fit reward for your obedience.

[24] Here then are a few points I have written down to provide you with a standard of conduct to live up to; but our Lord, at his second coming, will reward anyone who does more than he is obliged to do. See that the bounds of common sense are not exceeded, however, for common sense is the guide of the virtues.